For me, and for many others, the horror started with a floating vampire boy.

I was at a family sleepover at my Aunt Becky’s house. My cousins and I were in her basement watching the CBS adaptation of Stephen King’s novel ’Salem’s Lot. I was six—the youngest cousin present. There are actually three scenes with a floating vampire boy, but the one that got me was the third. The boy, materializing in the night amid thick white fog, hovers outside his friend’s bedroom window. “Open the window, Mark,” he begs. “Please! Let me in.” Mark, as it happens, is also my name. My little-kid mind could hardly take it. I was shocked, petrified.

I was also, in the fullness of time, hooked.

There’s a fair amount of material to be hooked on. There’s the 1975 book, King’s second novel, in which the author’s stated intention was to crossbreed the small-town drama of Peyton Place with the vampire horror of Dracula. There are two direct adaptations of the novel, namely the CBS miniseries and a later TNT miniseries. There are two related short stories by King, as well as two indirect adaptations of the novel. The fictional town of Jerusalem’s Lot, Maine—’Salem’s Lot, for short—has proven to be one of King’s most enduring and adapted creations.

Chapelwaite, a ten-part Epix series set to premiere on August 22, marks the latest adaptation. It stars Adrien Brody and Emily Hampshire and is based on one of the short stories. Also in the works is a James Wan-produced feature film based on the original novel.

In honor of Chapelwaite, but also because the time is always right to revisit Stephen King’s classic early fiction, let’s take a trip back to Jerusalem’s Lot. What makes the original novel so special? Is the CBS miniseries truly as amazing as people remember? Is the TNT version really as middling as its reputation? How does the story speak to our current Covid era here in 2021? Lastly, definitely not leastly, who the heck is Space Worm?

These questions, and many others, will be answered as we embark on a spoiler-filled, highly personal, deeply subjective overview of the ’Salem’s Lot universe. I’ll bring the crucifix, you bring the holy water. We’ll start, of course, with the novel, follow it with the two miniseries, and then go from there.

Strap in, horror fiends. Our journey begins…

The Novel

’Salem’s Lot centers on Ben Mears, a recently widowed young writer. It’s a vastly omniscient novel, dipping into the minds of over a dozen characters, but Ben is the focal point. He spent part of his childhood in Jerusalem’s Lot and now, at the novel’s outset, moves back to the sleepy country town. It’s early fall. Ben is haunted by a motorcycle accident that left him unharmed but killed his wife. Also, as a child, he had a traumatic experience in the Marsten House, the town’s infamous creepy abode and the novel’s symbol of the lingering, festering nature of evil. Ben’s motivation in returning is partly nostalgic, partly cathartic. He hopes to recapture the magic of his childhood and also to purge his demons by writing a novel inspired by the Marsten House.

“If there was a home, it had been here,” King writes as Ben drives into town. “Even if it had only been four years, it was his.”

Worst homecoming ever? Maybe. Oh, things are pretty stellar at first. Ben dates local artist Susan Norton and makes fast friends with schoolteacher Matt Burke. He’s cranking out his manuscript pages. But then a boy, Ralphie Glick, goes missing. The police consider Ben a prime suspect, along with also new-in-town Richard Straker and Kurt Barlow. The two run a furniture shop and live in the Marsten House, which was last occupied by the occult-obsessed gangster Hubie Marsten, who killed himself and his wife. Straker and Barlow’s true intent, revealed in slow, queasy fashion, is to vampirize the town. Yikes! Barlow is an ancient vampire, Straker is his human familiar. Ben, Susan, and Matt, early believers in the vampire crisis, gather up stakes and crosses and vow to save the town. They are aided by three others: Jimmy Cody, a quippy doctor; Father Callahan, an alcoholic priest; and Mark Petrie, a pre-teen classic monster fan.

As horror, the novel is scorching. The first half, in which Ben settles into his new life, oozes with uneasy foreboding. A long early chapter focused on a single day, consisting of twenty sections, each time-stamped and centered on a different character, alternates scenes of ordinary small town life with scenes of encroaching evil. It’s a brilliant gambit. The novel’s second half, in which vampirism spreads while Ben and his friends try to stanch it, unleashes one fearful scene after another. It’s a master class in plot complication. Sunset—the vampire’s wake-up time—is always looming. Virtually anytime the group settles on a plan, some horrific setback occurs and they have to scramble to make a new one. Indeed, the rails are truly and viciously off, here. Matt dies. Jimmy dies. Susan is vampirized. Ben, her grieving lover, is obliged to stake her. If you like horror that’s fun and frictionless, ’Salem’s Lot is not the book for you. It’s a dread factory.

But dread is by no means the only emotion here. Indeed, the novel has surprising psychological depth. King, in this book and elsewhere, particularly excels at grief-stricken aftermath. The novel begins with a flash-forward to Ben and Mark after they flee the town together; they’re depicted as survivors of an unspecified trauma. This sets the tone. Father Callahan’s grief is among the most vividly rendered. Callahan, hideously demoralized by Barlow, is last seen as a numb wreck of a man, stumbling onto a bus headed out of town and planning a never-ending bender.

It’s a great novel. It crackles with imagination. The story is fantasy but the emotions are real. It’s by no means perfect—we’ll get to its flaws later—but overall, it’s a blazing work of fiction.

CBS Miniseries

The original adaptation first aired in 1979 as a four-hour two-parter. The most obvious change to the book is Barlow. Here he’s portrayed as an unspeaking, Nosferatu-like monster, whereas in the novel he’s a chatty, human-looking sophisticate. Although Stephen King hated this change, it does serve to differentiate Barlow from Straker, who blend slightly in the novel. To my mind, a more regrettable change is Ben’s degree of past trauma. Neither his status as a widower nor his childhood Marsten House experience are mentioned more than once or twice. This change dampens the novel’s grand irony: that Ben, in seeking to be cleansed of past wounds, instead receives fresh ones. It recalibrates the story. Indeed, the original story is so condensed and rearranged that keen fans of the novel might find it slightly discombobulating to watch.

But it’s nevertheless a smart, vastly creepy film. Director Tobe Hooper has a confident, fluid style and knows exactly where to put the camera during horrific moments. The music score echoes Bernard Herrmann’s greatest hits. The Marsten House enticingly resembles the Psycho house. Its interior is an icky marvel: all dark decay and sickly green moss. David Soul, Lance Kerwin, and Bonnie Bedelia are solid in the primary roles of Ben, Mark, and Susan, respectively. But if there’s an acting MVP, it’s James Mason as Straker. He oozes dapper menace. There’s a great setup and payoff to Mark’s obsession with horror and magic: having failed to impress his father with his ability to escape any knot, Mark later gets tied up by Straker and then, yep, escapes the knot. Dad thought magic was useless. Dad was wrong! Parents, man. Sheesh.

And the vampires? They’re straight-up ghastly: bright-eyed, pale-faced, now grinning, now hissing. The floating vampire boys self-generate fog the same way Pig-Pen self-generates dust. This is silly in theory but chilling in practice. There’s a surprise ending with vampire Bonnie Bedelia, her body prone, her speaking voice eerily distorted, that’s sinister AF. The vampires wrecked me as a kid. To help calm me, one of my cousins created Space Worm, a kind of intergalactic support animal. More about Space Worm later.

Still, the adaptation isn’t quite full-throttle great. The director fouls up on some basics. The town, for instance, is inexplicably meager and underpopulated. We see the downtown, the cemetery, and not much else. It’s as if Straker and Barlow’s grand scheme is to take over a few blocks. The blocks don’t even have much bustle; at times it feels like Hooper forgot to hire extras. Toward the end, the daytime streets are vacant because the townspeople are now undead daysleepers. But there’s hardly any shock conveyed because there’s hardly any difference. Another problem is that characters and relationships aren’t ultimately that important to Hooper. Some of the early dialogue scenes are indifferently directed. Our heroes are likable but their anguish never fully becomes ours. The adaptation is scary because the premise and the vampires are scary. It doesn’t have that extra dread factor that comes into play with characters we’re deeply attached to.

There are actually two shorter edits of this miniseries. After its first airing in 1979, the two-part series was condensed to fit a single three-hour TV presentation. This version is currently unavailable. There’s also a further condensed version that was released as a feature film overseas. It moves fast, includes bloodier alternative takes, and doesn’t make much sense.

TNT Miniseries

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n4e24m-LYl4

The more recent adaptation, a four-hour two-parter first shown in 2004, follows the book more closely. Barlow the vampire (Rutger Hauer) is as much of a chatterbox as he is in the novel, which reduces the role of Straker (Donald Sutherland). The structure is essentially the same as the book’s, and some of the dialogue is lifted straight from the text. Ben Mears (Rob Lowe) is no longer a widower, but his childhood trauma at the Marsten House is actually amped up and expanded. In the book, child Ben enters the abandoned house on a dare and sees a terrifying vision of the long-dead Hubie Marsten. In this adaptation, he enters the house on the actual day that Marsten kills himself and his wife. He witnesses at least part of it. If that weren’t bad enough, Ben feels responsible for the death of a child that Marsten, a rumored child-killer, kidnapped and dumped in the bathtub. So the novel’s emphasis on past wounds is definitely retained.

But this version also updates the story, relentlessly. Characters refer constantly to the internet. Ben writes political non-fiction instead of novels. Ben is moody, but he’s not the only one. Indeed, most of the characters here have an aughts-style ‘tude. Matt the teacher (Andre Braugher) is antagonistic. Mark the youngster (Dan Byrd) is surly. This town would be a cruddy place even without the vampires. To be fair, the novel has mixed feelings about small-towners. But in this version the heroes aren’t even particularly likable. And director Mikael Salomon has a frenetic, overloaded, “modern” style. He’s not happy unless five things are going on at once. He zooms, he shock cuts, he jams in voiceover. There’s energy but not always intelligence. Ben’s grief over his Marsten House experience has some resonance, but the hectic, stroboscopic flashbacks to the actual experience are major duds. They’re like scenes from a bad video game.

And yet, the film does cast a spell. The vampires, who often swoosh and scuttle about, are all too clearly CGI-enhanced, but they’re still pretty freaky. Group vampire attacks, such as on a school bus or at the town dump, are particularly unsettling. There are several memorably striking WTF moments. A boy licking his sleeping mother’s bloody wrist. A vampire wedding that’s equally sweet and grisly. And by the end there’s absolutely a sense that this is a fully populated town and that the vampires have taken it over. A few characterizations stand out. Susan, as played by Samantha Mathis, is a rare bright light in this glum crew. Mathis is even touching as a vampire. And Father Callahan, played by the great James Cromwell, has a shocking, not-in-the-book arc.

Miniseries Cage Match!

If there’s only room in the canon for one of these miniseries, I’d definitely vote for the 1979 version. The vampires are among the scariest ever. James Mason’s Straker is a villain for the ages. But I do wonder how the film would play with people who didn’t grow up with it. The 2005 adaptation, for better and worse, is pacier and grabbier. And again, it absolutely has its merits, including a haunting score featuring vocals by Lisa Gerrard from Dead Can Dance. It also has an effective wintery vibe, a striking contrast to the spring setting of the 1979 version.

Just for kicks, I decided to get a few other opinions. My girlfriend Alicia, who had never even heard of ’Salem’s Lot before she met me, strongly prefers the 1979 version, mostly because she thinks the vampires are scarier and the characters have more charm. My nephew Ethan, however, a college sophomore and a big Stephen King fan, has a different take. He’s watched the 1979 version before and found it slightly boring. At my request, he rewatched one of the floating vampire boy scenes. His reaction: though it’s definitely a classic scene, visual effects have come a long way since then. He hasn’t seen the 2004 version but, on the basis of its trailer, thinks he might like it better. This is fair. The original adaptation, impressive as it is, doesn’t completely transcend its era. It’s no surprise that a youngster like Ethan would find it a bit creaky.

In any case, neither adaptation is definitive. Neither really captures the book’s sense of love and friendship among the core group of vampire fighters. That’s one of the most Stephen King things about the novel, so it’s ironic that these adaptations don’t make it a priority. And neither version fully captures the novel’s excellent High Noon-style obsession with the clock. Only one hour till sunset! Shit! And both versions lack the novel’s intricate gamesmanship—the ongoing strategizing among the heroes as they try, and usually fail, to outsmart Straker and Barlow.

Not that the novel is perfect. Timelier than ever, but not perfect.

The Novel – Further Thoughts

Larry Crockett, the town’s wealthy real-estate developer, retroactively pops as a Trump figure. Consider this: Crockett is more lucky than smart. He’s got a thing for hamburgers. He ogles women. He screws over the poor and elevates the devious. Indeed, if it weren’t for him, Straker and Barlow might never have come to town. When Straker offers Crockett a sweet but obviously crooked deal in exchange for the Marsten House and the furniture store, Crockett knows Straker’s up to no good but can’t pass up the money. When his employee finds evidence that implicates Straker in the disappearance of Ralphie Glick, Crockett pays him to keep it quiet. Here, as in the real world, money is the grease that keeps the wheels of evil turning.

And when evil takes hold in the town of Jerusalem’s Lot, the novel starts to evoke our own current Covid era. Not to the extent of King’s overtly pandemic novel The Stand, obviously, but still, the parallels are here. Vampirism has infiltrated the community and is spreading rapidly. People infect each other. The infected—viciously ill in the days before they turn—are scared and confused and exhausted. The crusade by Ben and his friends to save the town would be greatly helped if more people recognized that there’s a serious, hideous problem that has to be faced.

Still, as timely as the novel is, and as much as I love it, I’d be lying if I said it was flawless. The prose, though often amazingly vivid, is occasionally first-draft functional. But that’s a minor issue. Probably most long novels are inconsistently written. There are bigger problems here.

One major problem is exposition. Do you want to hear the entire history of Jerusalem’s Lot? No? Tough noogies. Take your seats, y’all. Class is in session. King has said that he wanted to make the town seem as real as possible, which is absolutely the right impulse. But he goes too far. Indeed, on my recent reread, I was surprised by how often, especially early on, scenes devolve into overly detailed exposition dumps. An early section entirely devoted to town history and geography, though denser than necessary, is actually pretty absorbing. It’s only when King tries to shoehorn informational overviews into the main narrative that things get clunky. Many early scenes, such as when Ben first enters town or when he and Susan drive home from their first date, are overloaded with street names, character names, and history. The mythology is great but the detail can be exhausting. At one point, King gives us the backstory of a furnace grate.

An even more egregious problem is the portrayal of the working-class characters. Too many of them are bigoted, ignorant fools. I forget this aspect of King sometimes—that his early work has a condescending, mean-spirited streak. The most uncomfortable character here is Dud Rogers, overseer of the town dump. Dud is a grotesquely depicted hunchback whose inner life is rife with hatred for women and gay men and whose prime joy in life is shooting and torturing dump rats. So through a single character, we get ableism, homophobia, and misogyny, along with a dose of animal cruelty. Stupid characters energize King; the writing comes alive in a way it doesn’t always with the smart ones. So there’s a sense that, although he’s clearly mocking them, he’s getting a kick out of spouting their nastiness. It’s hard to know what to make of that.

So, yeah. Great book! Absolutely! But also flawed and problematic.

Related Short Stories

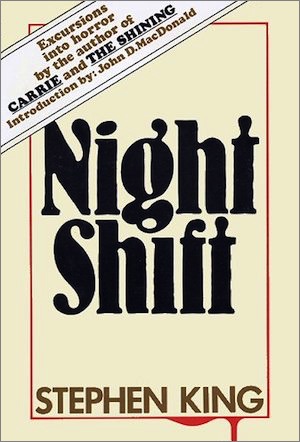

“One for the Road,” featured in King’s debut story collection Night Shift (1978), takes place a few years after the novel and is set in an adjacent town. Booth, the narrator, is drinking at his pal Tookey’s bar on a blizzarding winter night. They’re old men. A stranger bursts into the bar, frantic. The man, a young husband and father, explains that his car got stuck in the snow and that his wife and daughter are in it. Booth and Tookey gradually realize that the car is stranded in the vampire-infested Jerusalem’s Lot. Very reluctantly, they decide to drive out into the blizzard and try to save the wife and daughter.

“It’s the wind I don’t like,” Booth tells us, “when it picks up and begins to howl, driving the snow into a hundred weird flying shapes and sounding like all the hate and pain and fear in the world. There’s death in the throat of a snowstorm wind, white death—and maybe something beyond death.”

It’s a stunner of a story. It should be taught in writing classes. It’s propulsive, it’s atmospheric, and it has a distinctive character voice. It’s about aging as much as it’s about vampires. It’s about wanting to do the right thing, despite severe danger and the strong likelihood that it’s not going to make a damn bit of difference. And it’s the only real sequel we’re likely to get. King had originally planned to write a full sequel novel, but after continuing the story of Father Callahan in The Dark Tower series, the author decided that there was no longer any need.

***

“Jerusalem’s Lot” is the basis for the new Chapelwaite series on Epix. The short story takes place in the mid-1800s, a full century before the events of the novel. Talk about a prequel! The story centers on Charles Boone, inheritor of the family mansion of Chapelwaite in the town of Preacher’s Corners. The tale is told entirely in letters and journal entries, with the bulk of the text being Boone’s missives to an old friend. Chapelwaite is majestic but also unsettling. There are grotesque statues on the lawn, rats scurrying in the walls. Or maybe something worse than rats?

“Developments of a disquieting nature,” Boone writes to his friend after living in Chapelwaite for a few weeks. “The noises in the house have intensified, and I am growing more to the conclusion that rats are not all that move within our walls.”

It’s a weird, creepy, awesome story. Boone, a widower with a history of instability, uncovers a strange family legacy that involves not only Chapelwaite but also the desolate nearby town of Jerusalem’s Lot. The story, also collected in the excellent Night Shift, is often characterized as a gloss on Lovecraft, but it’s always struck me as resembling a long-lost work by Poe or Hawthorne. There are some beasties here, including a monstrous worm—not to be confused with Space Worm—as well as decaying undead corpses. No overt vampires, though. The story connects to the novel only by virtue of its setting and its reinforcement of the idea that evil lingers in a place. Jerusalem’s Lot, it turns out, was foul long before Straker and Barlow, or even Hubie Marsten, came to town. Then again, it’s possible that Boone’s madness has returned—that some or even all of the evil he describes in this story is merely his fevered imaginings.

Other Adaptations

A Return to Salem’s Lot (1987), a feature film that didn’t get much of a theatrical release, is a quasi-sequel to the original CBS miniseries. It’s a low-budget production directed by genre veteran Larry Cohen. An anthropologist played by Michael Moriarty, who grew up in the titular town, moves back there with his son in tow. They discover that the town is now run by a clan of seemingly benign vampires. They drink animal blood rather than human blood. The vampires want to gain respect from the larger world; they want Moriarty to document their history. Moriarty, proudly amoral, considers it but soon discovers—shocker!—that the vampires can’t be trusted. For lovers of schlock, the film is worth a look. For everyone else, it’s a hard pass.

The Hulu series Castle Rock, which remixes several Stephen King tales, features the town of ’Salem’s Lot in its gloriously overstuffed second season. Originally released in 2019, the season includes among other storylines a mysterious plot brewing at the Marsten House. Given the town and the house, we might rightly wonder when the vampires are going to show up, which (spoiler alert) they never do. No matter. It’s a great season anyway. Among its many highlights is a terrific performance by Lizzy Caplan as a young Annie Wilkes, the obsessed fan from Misery.

***

Back to the family sleepover at Aunt Becky’s house.

At one point, my cousins and I were upstairs watching the CBS version of ’Salem’s Lot with the grownups. I watched with sick wonder, drenched in fear. My Aunt Brenda, an empathetic nurse who perhaps sensed my unease, cheerfully commented on the ingenuity of the special effects. Maybe it was meant as a grounding device—a way of reminding me that the show was fictional. But I was way beyond that. It wasn’t a show I was watching. It was happening to me.

Later that night, back in the basement, my cousin Matt repeatedly hissed like a vampire, just to torture me. Matt had a lot of great qualities but mercy wasn’t one of them. His older brother Sam, though, came to the rescue. He created Space Worm, enemy to vampires, protector of cousins. In his sleeping bag, or “snuggler,” as our grandma referred to them, Sam wormed around on the floor, calling out that he’d stave off all vampires. It was funny. It helped. But I still ended up dragging my own snuggler upstairs and sleeping outside my parents’ room that night.

It wouldn’t be the only night I slept outside my parents’ room because of the memory. Indeed, I regularly prayed that I wouldn’t dream about vampires. I did anyway, and once even had a full-blown night terror about them. I’ve since wondered: Was I legit traumatized? And where the hell were my parents at that family sleepover? Although, in their defense, no one was forcing me to watch. In any case, my high-octane fear eventually melted into a lower-grade one. At twelve, I read the novel ’Salem’s Lot for the first time. I was deeply freaked but also totally fascinated.

Soon after, I got my mom to read the book. She found it silly and riveting. One of her complaints regarded Susan and Mark’s decision to enter the Marsten House and face down Barlow on their own. My mom was all, “What a dumb thing for Susan to do!” My mom was right, of course. Mark has the excuse of being a child, but Susan is a fully grown, intelligent adult. Then again, fiction thrives on dumb decisions. If characters never did anything rash, there would be no novels. And Susan’s dumb decision leads to such great stuff, including a subsequent scene in which a vampirized Susan appears at Mark’s bedroom window. Susan tries various tactics to get him to invite her in, at first saying that vampire life is kinda cool after all, then offering to kiss him romantically, and finally reasoning that there’s no escape, that he’ll either be her victim tonight or someone else’s on another night. She’s like an addict trying to score money for a fix.

Mark sends her away. His thoughts are along the lines of, Wow. This town is so screwed. And indeed it is. Mark will survive the ordeals to come, but not without major scars to his psyche.

Stephen King gets trauma. He depicts the interiority of these characters so thoroughly that we’re right there with them. ’Salem’s Lot is booby-trapped with their grueling memories. When Ben learns that Susan has been vampirized, the fresh trauma retriggers an old one, the death of his wife. King plunges us into the memory. Ben and his wife, both thrown from the motorcycle he was driving, are on the ground. Ben gets up and dazedly walks over to his wife—who will never get up. His body floods with icky sensation, his mind struggles to compute what’s happened. It’s a great scene, something any writer would be proud of. It’s such an astute, up-close look at the horror of losing a loved one that it stops you cold. It’s even scarier than the vampires.

Mark Benedict is a graduate of the MFA Writing program at Sarah Lawrence College. When not reading Stephen King, he’s rewatching Don’t Look Now or Let’s Scare Jessica to Death.

It is a great book, maybe it’s time for a re-read. I do remember there’s one scene in it that’s really hard for me to cope with, can we do spoilers here?

Okay, well, I’ll just be vague then: the mom feeding her baby some chocolate pudding. Oof.

Read it several times, watched the TNT miniseries (and had many of the same issues with it as outlined here), never saw the first. Two scenes stay with me to this day, as examples of two different kinds of horror. The first is Susan at Mark’s window, crooning and evil and tempting. “I’ll kiss you, Mark. Kiss you all over like your mother never did.” The second is the one brief dip into the mind of Salem’s Lot’s pastor (not Father Callahan), and his terrible, explicit fantasy of the girls’ Sunday School class.

The reason that people connect King’s story with Lovecraft and the Cthulhu mythos is King’s use of the grimoire “De Vermis Mysteriis” which originated with Robert Bloch and was mentioned several times by Lovecraft.

Of course, we meet Father Callahan again, in Wolves of the Calla…

A great overview. (Hurrah for Space Worm!)

I vividly remember begging my mother to allow me to watch this as a youngster back in the early 80s when it came on the telly. Much to her post-event annoyance, she did allow me to watch it, and I don’t think I slept properly for a month. The boy at the window and the appearance of Barlow at the jail – my gods, that was the stuff of nightmares ….

The book (and short stories) and the 1979 movie are among my favorites. I have long since come to dislike how a lot of current (for the past couple of decades) have presented vampires as, more or less, sex gods instead of the horrors and monsters they really are. So, the older works are some of my favorites regarding them.

As for being traumatized at a young age by a horror movie… I can sympathize. I remember watching the old 1950s B-Movie Fiend Without A Face at the tender age of 5 – and I watched it mostly alone. It not only scared me, but set my love for monster movies and horror for life!

I know Lugosi was not monstrous to look at, though the rip-off played by Max Schreck, Count Orlock was. Christopher Lee was menacing but I suppose had a sexy aspect. Lestat is extreme but Rice’s vampires run the gamut and all we see besides the family in Interview are at least playing the monster role at the theater. Of course, she turns them all into Real Housewives before she is done.

I was in junior high for this one and to have been on TV (which meant a big three network or UHF) at that time, it was pretty horrifying. The boy in the window stuck with me.

@8 Re Lugosi, it can be hard to imagine today, but at that time (late 1920’s – early 1930’s), that kind of “exotic foreigner” persona was considered sexy and alluring, as seen in many other movies of the period (e.g. Rudolph Valentino, Charles Boyer, etc.).

Um? Ripoff? Nosferatu proceeded Dracula (the films, which what I assume you are talking about) by nine years. Nosferatu came out in 1922. Dracula in 1931. Even his appearance in the stage play was in 1927. So I’m not sure how Orlock in Nosferatu rips off Dracula.

10: They ripped off Stoker published in 1897. His heirs sued and won and the film was ordered destroyed. I am glad it wasn’t but it was a rip off.

@11

Yes, but you referenced Lugosi, not the novel. But you are correct about the ruling. Of course, the film still exists and some consider it superior to the Lugosi version. Personally, I think both are excellent.

My bedroom wall was sliding glass patio doors. After that movie, it was IMPERATIVE that I close the curtains before it got dark.